This is far and away the longest article Mr Blundell has ever republished.

I extend my public thanks to American Journal

This public announcement display presentation would be for readers who have heard me speak this morning in the Adelaide Hills on the psycho-spiritual death of undergraduate Public Square^ chatter concerning the ghastly ‘gladiatorial’ 500 years to 2008 contest of pluralism and collectivism a useful jumping back point in patriarchic studies.

Have I myself read it, no. The first line in the ‘blurb’ or promotional schpiel named Oliver Wendell Homes one of the ‘Second’ or New-world’s grand and eloquent jurists. That did me.

John

Thematics logic, neurocognitive health, internet reform, economy, education, have-a-good-day

Winter 2025 / Volume IX, Number 4

The Making of a Techno-Nationalist Elite

By Tanner Greer

REVIEW ESSAY

The Technological Republic:

Hard Power, Soft Belief, and the Future of the West

Alexander Karp and Nicholas W. Zamiska

Crown Currency, 2025, 320 pages

America has gifted mankind two great patrimonies. The first is a familiar set of institutions and ideals. These are crystallized in our civic catechism, captured in certain phrases: “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” or “government of the people, by the people, for the people.” The institutions (constitutions, legislatures, courts, and so forth) that realize these ideals have had immense global influence.

Democracy, despite the challenge posed by alternative systems, remains the global default. This would not be true if Americans had not first proven that democratic governments could endure. We were the first people to gamble the fate of our nation on Enlightenment ideals and the first to demonstrate that those ideals could serve as the foundation for a stable political order. Two centuries on, American poets and politicians still celebrate this improbable achievement.

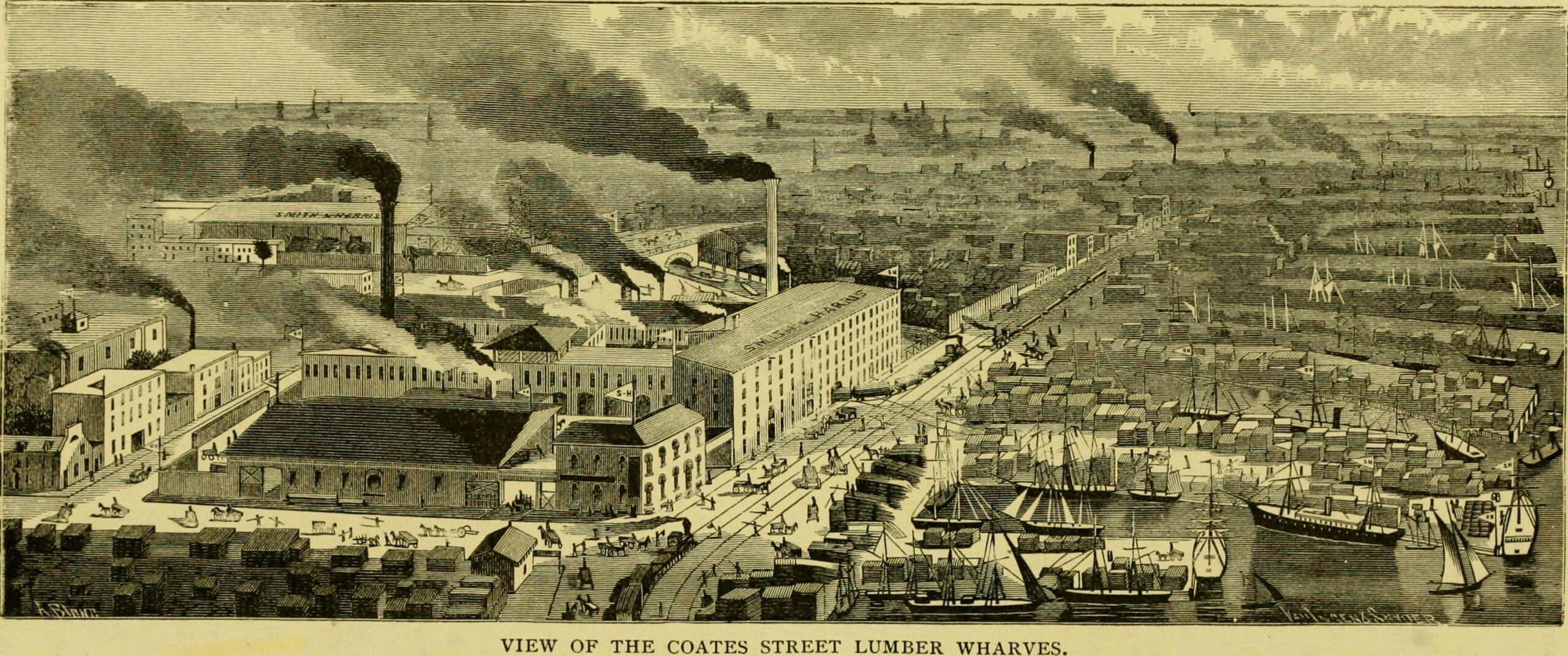

Americans are less proud of their second gift to the species. Yet on the civilizational scale, this second contribution may be more consequential than the first. It was the American people who first leapt from the agrarian age to industrial modernity, a revolution whose importance is only rivaled by the invention of agriculture itself. This revolution replaced mules with machinery, lamps with electricity, and bricks and wood with concrete and steel. Humanity would henceforth live in a world of wires, engines, and endless acceleration. This world had no precedent in human experience. It was a world built by the United States of America.1

The scene was prepared by the British, whose inventors harnessed steam power during the First Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. But the inventions that make modern life possible emerged between 1860 and 1930.2 These years saw the invention and diffusion of steam turbines, internal combustion engines, electric motors, alternators, transformers and rectifiers, incandescent light, electromagnetic waves, recorded sound, aluminum smelting, dephosphorized steel and steel alloys, reinforced concrete, nitroglycerin, synthesized ammonia, radio transmission, plastics, and gas turbines. The architecture of our industrial civilization was assembled within one lifespan.

Americans did this assembling. The science that underpinned these technologies was international, but these technologies were refined, commercialized, and scaled in the United States. The Second Industrial Revolution unfolded as American industrialists built the corporate and financial machinery needed for industrial-scale production. Out of this crucible came not only new machines but new forms of management, bureaucracy, and social organization that, over the course of a century, would be imitated, adapted, and imposed across nearly every society on Earth. The United States was the birthplace of the technological republic.

By naming their new book The Technological Republic, Palantir executives Alexander Karp and Nicholas W. Zamiska gesture toward this heritage. The book comes at a unique juncture in Silicon Valley’s history. Its leaders have awoken to their status as a distinct social elite but remain uncertain as to what obligations that status carries. Their old “Californian Ideology,” half libertarian fantasy and half globalist prophecy, has collapsed. What creed will take its place is not clear.3 Few seem better placed to address these questions than Karp, a founder known as much for intellectual ambition as for entrepreneurial success. While leading a defense tech company, with close ties to the sitting administration, he and Zamiska are perfectly positioned to lay out a new civic philosophy for America’s technological elite.

Readers hoping for such a book, however, will be disappointed. The Technological Republic is not a serious exploration of the political foundations of technology, nor a study of the technological foundations of American power. It is not a sober forecast of technological trends or a reckoning with their implications for the American public. It is not even a business history of Palantir itself. The Technological Republic aims at something “substantial and ambitious,” inhabiting “the interstitial but we hope rich space between political, business, and academic treatises.”4 It reads like a collection of TED Talks. Its chapters are discrete and disconnected. The themes that tie them together are nowhere explicitly laid out but must be inferred by the reader.

The most persistent of these themes is a critique of Silicon Valley’s “engineering elite.” Karp and Zamiska insist that the fortunes and fame of this elite were not created ex nihilo. This class is, in fact, deeply indebted to the civilization that made their firms possible, one that most of them feel no kinship with or obligation to. At the center of that civilization is the United States. The American nation should demand the loyalty of those who prosper most from it. This loyalty should be freely given. Karp and Zamiska believe that tech leaders should focus their substantial talents on bettering this nation. Like Palantir, their firms should not shy away from the provision of public goods. Silicon Valley should boldly take part in the “articulation of the national project.”5 Alas, the instinct of the Silicon Valley founder is to move as the market lists. How does the market list? Toward “lifestyle technologies” whose main purpose is to “enable the highly educated . . . to feel as if they have more income than they do.” America’s engineering elite is brilliant, but their brilliance is wasted on baubles.6

These observations may be accurate, but the goal of The Technological Republic is to inspire American technologists to become American techno-nationalists. Regrettably, Karp and Zamiska offer no roadmap for accomplishing this. The two men invoke the technologists of generations past as archetypes the modern engineering elite might aspire to, but they do not investigate the religious, social, political, or economic milieu that created these technologists. This is unfortunate: Karp and Zamiska’s sermonizing is not sufficient to make patriots out of a generation of engineers who have never been trained to think of themselves as stewards of a state. Elevating Silicon Valley’s engineering elite into a governing class would require much more: institutions, alliances, and traditions that root the wealth and expertise of our technologists in service to the nation.

The United States has had such a class in the past. They were the architects of the Second Industrial Revolution: engineers, industrialists, and entrepreneurs who believed that a technological revolution was needed to propel America toward greatness. They were, in this sense, America’s first governing class of techno-nationalists. In the mid-twentieth century, Americans would label their descendants the “Eastern Establishment.” This class did not materialize out of thin air. Examining their origins, and the reasons for their seventy-year dominance of American business and government, provides a useful corrective to Karp and Zamiska’s fragmented thinking and hazy wishcasting.

The Genesis of America’s First Techno-Nationalist Elite

The techno-nationalist sees technology and nationhood as two intertwined goods. As technology advances, so does national power. Only a powerful state can unite a populous nation around a common identity and protect it from both external enemies and centrifugal forces. Such a nation then functions as a vast open market that allows emerging industries to benefit fully from economies of scale. These industries create wealth; wealth invested expands industrial capacity; booming industrial development stimulates the invention and adoption of new technologies, beginning the cycle anew.

This vision of techno-nationalist development has a long American pedigree. Alexander Hamilton described its essential elements more than two centuries ago. Hamilton predicted that American independence would last only if the thirteen American states fused their economies into one national market governed by an energetic executive. This government would spur industry, uphold American credit, and deter foreign predation. This was an explicitly industrial vision. He believed that “not only the wealth but the independence and security of a country appear to be materially connected with the prosperity of [its] manufactures.” Industrial development, in turn, required the security and scale that could only come from a large and unified nation. Hamilton argued that the U.S. Constitution would create this nation. By “bind[ing] together [our states] in a strict and indissoluble Union,” the constitution would “erect one great American system . . . able to dictate the terms of the connection between the old and the new world.”7

The Hamiltonian program for “one great American system” of growing integration, advancing industry, and rising power was not realized in Hamilton’s lifetime. While the U.S. Constitution laid the groundwork for a technological republic, it was not enough to bring one into being. What the new republic required was a national elite resolutely committed to their nation’s technological ascent. But it would take decades before a class with such techno-nationalist inclinations came to helm the American state and economy.

There were several reasons for this. Antebellum elites thought of themselves as the first men of their states, not as the first men of the Union.8 Most came of age in an era when communication between regions was slow and halting. A letter from New Orleans to New York, cruising the country’s waterways, could take a month to arrive.9 In such a world, elite social networks were centered in their local communities. The leading patriarchs of Philadelphia, New York, Charleston, Baltimore, and Boston did not marry beyond state lines.10 Elite universities were anchored just as firmly in their regions. For instance, more than 70 percent of Harvard students were born in New England well into the 1870s.11

Commerce lacked the weight, and industry the reach, to forge a constituency for national integration. Most antebellum corporations were chartered by individual states and were required to ply their trade within state lines.12 The defeat of the Second Bank of the United States in 1832 left the country a fractured financial mosaic, its credit system a patchwork quilt of competing state-based institutions. Even with the advent of the railroads, uninterrupted transportation for more than a hundred miles was rarely possible. Most antebellum railroads were locally built and used completely different gauges. The system was fragmented between hundreds of competing lines. By 1860, no more than half a dozen crossed state borders.13

Geographic distance was compounded by cultural rifts. The United States was founded by a variety of settler cultures, each with distinct views on virtue, freedom, and honor.14 These cultural cleavages persisted into the nineteenth century, sparking tensions wherever pioneers from different backgrounds settled in close proximity.15 The Congregationalism of the old Boston Brahmins contrasted sharply with the Anglicanism of the Tidewater aristocrats and Philadelphia merchants; both were distinct from the Methodist and Presbyterian creeds which dominated the Midwest and the Scots-Irish backcountry.16 Orators played up these differences and often framed political debates as battles between culturally and economically distinct regions, such as “the North,” “the West,” and “the South.”17 In this environment, Washington was, like Brussels today, less the seat of a cohesive governing elite than a forum where representatives of competing polities met to hammer out deals.18

The most significant fissure split the slaveholding South from the rest of the republic. For decades, influential southerners were dogged enemies of national integration, fearing it might erode the stability of their “domestic institution.”19 These forces controlled the balance of American power. Eight of America’s first fifteen presidents hailed from the South; in twenty-four of the thirty-two years that preceded the Civil War, the presidency was controlled by the Democrats, whose party was dominated by southerners. The strength of the slave power not only reinforced the localist, antinationalist thrust of American politics, it also fueled fierce resistance to any national program of technological development. Southern elite life revolved around counties, not cities; agriculture, not industry; and the export of raw materials, not the import of foreign capital. The Democratic press thus attacked proposals for industrial development with special venom.

A Hamiltonian economic program, declared Argus of Western America, “runs the whole round of the British devices to enslave a people.” The Southern Review told its readers that “ours is an agricultural people, and God grant that we may continue so. It is the freest, happiest, most independent, and with us, the most powerful condition on earth.” The Democratic Review was more venomous, calling it “almost a crime against society to divert human industry from the fields and forests to iron forges and cotton factories.” A Georgia newspaper was even more scathing: “Free Society! we sicken at the name. . . . The prevailing class one meets with [in the North] is that of mechanics struggling to be genteel . . . [but] who are hardly fit for association with a Southern gentleman’s body servant.”20

The fortunes of the wealthiest Northern families were yoked to the slave power; their politics often echoed its priorities. New York’s merchant houses served as financial brokers for the cotton magnates and their British customers. They had as much disdain for “mechanics struggling to be genteel” as the Southerners; their dealings and their wealth were oriented toward the Atlantic, not the American interior.21 The other great bloc of Northern wealth, the tight-knit dynasties who raised the textile mills of Lowell and Lawrence, confined their investments to New England. Their mills hummed only so long as the Southern plantations fed them raw fiber. The coalition they formed with Southern planters (what Charles Sumner would scornfully call “the lords of loom and the lords of the lash”) further magnified Southern political power.22

The wealthiest elite groups of the antebellum era thus resembled Karp’s picture of the contemporary tech elite: they were suspicious of executive power, distrustful of American nationalism, insulated from the American public, and focused their investments in whatever field promised the highest returns, regardless of the political consequences for doing so. Many were localists; some were Atlanticists. Almost none were nationalists. Their favored politicians, men like Franklin Pierce, William Marcy, Howell Cobb, and James Henry Hammond, dismantled America’s system of centralized finance, slashed its tariffs, vetoed internal improvements, shoved industrial policy down to the states, and maligned the rising class of industrialists.

America’s most powerful regional elites simply had no material stake in a technological republic, and they lacked the nation-spanning institutions or social networks needed to lead one. The handful of antebellum statesmen who, with Daniel Webster, urged Americans to become “one people, one in interest, one in character, and one in political feeling,” were rewarded with a lifetime of political disappointments.23 All of this would change with the Civil War.

The conflict elevated two social groups that had hitherto played second fiddle on the American stage: the disparate Northern regional elites, newly united beneath the Republican banner, and the rising class of industrialists and their financiers.24 The first seized the commanding heights of the Union’s politics; the second built the commanding heights of its economy. War bound them together in a common techno-nationalist project. The personal ties, institutions, and ideology that saved the Union would continue long after the guns went silent at Appomattox.

The ascent of this new elite class was hastened by the eclipse of its old rivals. With a few Maryland grandees excepted, the great planter aristocracy—ferociously hostile to both industry and the Union—followed their states in secession. Before their rebellion was over, the economic and political foundations of their power lay in ruins. Their ports were blockaded; their fields were stripped bare by marauding armies; their traditional customers found other sources of cotton; and emancipation, in a stroke, erased the largest store of Southern wealth.25 During Reconstruction, the plantation class was denied formal political power; after Reconstruction, they were only a junior coalition partner in the weaker national party. It would be a full century until any representative of a secessionist state would be elected president.

The Republicans of the 36th Congress moved quickly to exploit the absence of Southern obstruction. They advanced a legislative program which has since been called “the blueprint for modern America.”26 The package included vast land grants to transcontinental railroads, high tariffs to stimulate domestic manufacturing, and a host of measures designed to spur national development. As the Civil War stretched on, demand for iron, rail lines, machine tools, telegraph wires, steam engines, and armaments surged. The combination of new protective tariffs and the threat of Confederate commerce raiding ensured that domestic producers met this demand. For enterprising industrialists, this was an extraordinary opportunity to amass wealth on a scale that antebellum America had never offered.27

War also birthed a new kind of American financier. At the outset of hostilities, Washington lacked both the taxation machinery to fund its armies and the appetite to inflate away the nation’s currency. Instead, it turned to a rising class of bankers who marketed bonds in Philadelphia, Boston, and, above all, New York. These financiers, in turn, closely advised the federal government on how to design a national banking system capable of supplying the Union with a universal currency and a uniform system of credit.28 Young upstart J. P. Morgan began his ascent serving as one of these financial intermediaries.29 He was not alone in this. Out of the ten largest banks in New York City in 1870, five did not exist before the war.30

To a striking degree, the war effort was sustained through the voluntary efforts of the Union’s most prominent citizens. Some of these contributions, such as John D. Rockefeller’s sponsorship of thirty Cleveland soldiers, were individual.31 Others required association. Across the North’s largest cities, prominent citizens organized Union League Clubs, which functioned both as social clubs for nationalist elites and as political action committees for the Union cause. Through the course of the war, the members of the Philadelphia Union League Club would outfit “nine regiments, two battalions, and a troop of cavalry.”32 Its New York counterpart would print 900,000 Unionist pamphlets and would put New York’s first black regiment into the field.33

More impressive still were the efforts of the New York City Union Defense Committee, organized days after the first shots at Fort Sumter; it rushed workers to fix sabotaged rail lines, aided the families of poor conscripted soldiers, and raised a total of sixty regiments.34 The Sanitary Commission, a volunteer aid society led by the same upper-class northeastern elites that flocked to the Union League clubs, mobilized and trained thousands of nurses to tend to the North’s wounded and sick. A similarly organized Christian Commission provided religious literature and services to soldiers and sailors on every front of the war.35

The men who joined this effort drew from it a new national consciousness. “What I learned from the Civil War,” recalled Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., who served as a regimental officer in the Army of the Potomac, “was that Boston is just one city in America.”36 It was a lesson learned by many young Boston Brahmins on the frontlines. Of each class that graduated from Harvard between 1855 and 1861, between a third and a half went to war.37 They were thrown into a great melting pot of young northeastern patricians. Of 120 Union staff officers who were not West Point graduates, ninety-three were natives of the New England states, New York, and Pennsylvania; of 134 cavalry officers, seventy-three were natives of the Northeast.38 There, working in close contact with commanding officers who had earlier worked with the regional railroads, these young men would gain firsthand experience with the industrial methods of organization, logistics, and accounting that powered the Union war machine. And they would not forget these skills when they returned to civilian life. As historian George Fredrickson observed, the war transformed them “from a demoralized gentry without a clearly defined social role [in national life] into a self-confident modernizing elite.”39

This would shock and disconcert their fathers and grandfathers; most were still devoted to the romantic individualism that had dominated American culture during their own youth.40 The Civil War thus marked a decisive generational turning point. Most Union generals were in their thirties or forties when they assumed command; their junior officers were younger still. Nor was the Union’s civilian leadership dominated by elder graybeards. In William H. Seward’s words, at the dawn of the Civil War, the Republican Party was “chiefly a party of young men.”41 Wall Street saw it the same way. One prominent financier later recalled that the struggle to mobilize finance occurred just after the panic of 1857, during which the “old conservative element [of Wall Street] had fallen . . . and its place supplied by better material and with young blood.”42 The Civil War both elevated a new generation of elites into public life and served as the crucible that defined their worldview; they would carry this worldview with them through the rest of their public careers, which often stretched well into the twentieth century.

Few understood the significance of these developments better than Frederick Law Olmsted, a pivotal figure in New York politics who founded the city’s Union League Club and served as the first secretary of the Sanitary Commission. Reflecting on the Club’s mission, Olmsted compared its members with rebel plantation masters, who fought to protect a “legally privileged class” modeled on European nobility. In contrast, the Union League Clubs represented a “true American aristocracy.” This democratic gentry would be composed partly of “men of substance and established high position socially . . . men of good stock, or of notably high character . . . and especially those of old colonial names well brought down.” But it must also draw in “promising young men—quite young men, who should be sought for and drawn in and nursed and nourished with care, but especially of those rich young men . . . who don’t understand what their place can be in American society.”43

The rebellion had shown these young men what that place might be.44 Republican politicians, army officers, industrialists, and financiers had been thrown together by common cause. In the sweat and strain of wartime administration, these young men worked shoulder to shoulder. They met in committee rooms and counting houses, in field headquarters and Union League clubs. In the process, they formed bonds of trust that endured long after the Civil War’s close.

In war, they had saved the Union. Now, they would build its strength in peace. Their task was to stitch the continent into a single market, to tie its farms and cities together with railroads and telegraphs, and to develop new American industries, thereby empowering the American people on the world stage. They would be the architects of a new, continent-spanning technological republic. Such an ethos would sustain America’s new elite through the Gilded Age.

Consolidation of a Techno-Nationalist Elite

The partnership between Northern industrialists and political leaders only deepened in the postbellum years. Both groups “embraced continental integration as a heroic undertaking and infused it with an exhilarating sense of grandiosity.”45 Their solidarity was expressed in political alliances, reinforced by common schools and civic clubs, and deepened through widespread intermarriage. By the end of the Gilded Age, it no longer made sense to speak of them as two separate camps. They had fused into one governing stratum: the “Eastern Establishment.”

Consider the composition of Theodore Roosevelt’s cabinet. Before he served as Roosevelt’s postmaster general or the chairman of the Republican National Committee, Henry Clay Pyne worked as both an electricity and railway executive. He was not the only railway or electricity executive in the cabinet: Roosevelt’s vice president, his first secretary of the interior, and two of his Navy secretaries had been railway men, while his first secretary of commerce and second postmaster general both served as the presidents of electric utilities.

The cabinet also included several accomplished industrial lawyers, among them Victor Metcalf, Elihu Root, and Philander Knox, who began his career representing Andrew Carnegie. Before he led the State Department, Robert Bacon managed J. P. Morgan’s steel and railroad interests; Lyman Gage, in contrast, would leave the administration to serve as the president of U.S. Trust. Even the literary-minded John Hay, who never held a corporate job in his life, was thoroughly enmeshed in the world of industry by way of marriage: his wife was Clara Stone, daughter of Ohio railroad mogul Amasa Stone. During the Second Industrial Revolution, the families that governed the United States and the families that captained its industries were one and the same.

This was America’s first techno-nationalist elite class. Their nation-building program, and the fortunes that sustained it, demanded coordinated action across economic, political, social, and cultural fronts.

In the years following the Civil War, the vast financial machinery built to market war bonds now opened its coffers to the railroads, telegraph companies, and manufacturing. The scale of expansion was extraordinary. In the seven years after the Civil War, the number of American factories doubled. By 1873, $400 million dollars had been invested in manufacturing capital, four times the amount invested in 1865. It only took four years for the railroads to gather $500 million dollars in new investment. To handle this boom in financial activity, the number of bankers in New York City grew from 167 in the year 1864 to 1,800 in 1870. The railroad companies they invested in would lay thirty-five thousand miles of track over those same years, which amounted to more track than existed in the entire railroad network of 1860.46 That was only the beginning: by 1895, railroad capitalization was fourteen times the national debt, and four times all local, state, and federal debt combined. At that point, 183,601 miles of rail line had been laid, approximately 42 percent of the global total.47

The sheer volume of physical material that could now be produced, transported, and processed by these new technologies had no precedent in human history.48 Existing corporate forms could not manage the torrent. The railroads, which had to coordinate hundreds of trains moving across multiple states and time zones on a finite number of lines, were the first to confront the problem head-on. Their solution was to invent the modern corporation: vast, vertically integrated bureaucracies with multi-level, managerial hierarchies. These structures shifted decision-making power away from the decentralized marketplace and into the hands of salaried technicians and middle managers, creating a template that would define American business—and American power—for the next century.49

Corporate hierarchies gave businessmen, a profession created by this technological revolution, the tools to master scale. But scale alone did not guarantee profit. As technology proliferated, so did competition. Cutting-edge industries required enormous capital outlays, yet ruthless price wars drove returns downward. In this environment, financiers found it difficult to justify further investment in technological development. Once again, an organizational answer was found. Under the prodding of financiers like J. P. Morgan, firms first formed cartels or “pools,” then coalesced into trusts, and at last fused into horizontally integrated holding companies.50 Consolidations would reach a fever pitch in the years between 1897 and 1904, as 4,277 industrial firms were merged into just 257.51

America’s technological revolution could not have been possible without a corresponding revolution in legal doctrine. Before the Civil War, corporations were generally quasi-public bodies chartered individually by state legislatures to accomplish public aims. Their activities were confined to narrow public purposes, with their capitalization, geographic scope, and permissible lines of business limited by their charters.52 National industrial systems were not possible within this framework. The Second Industrial Revolution was premised on a legal architecture designed and defended by the Eastern Establishment’s jurists and legislators.

This great reformation began with a salvo of new laws across northeastern states that replaced incorporation through legislation with a standardized system of procedural filing. New legal statues provided directors and shareholders with nearly unlimited power to amend articles of incorporation, modify the character of their business, and modify the rights of classes of their shares. Northeastern states also relaxed restrictions on internal business operations, liberalizing the definitions of capital, surplus, and profits to enable complex corporate accounting practices, removing requirements to receive state permission to operate outside of the state, allowing corporations to hold stock in foreign state companies, and loosening merger requirements. This process went furthest in New Jersey, whose state legislature undermined trust-busting efforts by passing a general incorporation law for consolidated holding companies just before the federal Sherman Antitrust Act went into force.53

The courts strengthened the new corporations’ legal standing in a series of groundbreaking cases. Wabash v. Illinois (1886) barred states from regulating interstate commerce, leaving corporations largely free to operate across state borders. Reflecting back on the case at the dawn of the twentieth century, one legal analyst described its consequence: “in the last 30 years [the Commerce Clause of the constitution] has been so developed that it is now in its nationalizing tendency perhaps the most important conspicuous power possessed by the federal government.”54 Just as important may have been Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad’s (1886) formulation that corporations were constitutional “persons” entitled to due process and equal protection. When coupled with Chicago, M. & St. P. Railway v. Minnesota (1890) and Allegeyer vs. Louisiana’s (1896) substantive due process doctrines that barred rate regulation absent “just compensation” and prevented state governments from breaching “liberty of contract,” this doctrine “rendered many efforts to regulate economic activity impossible.”55

The effect of these decisions was to create a large, unified national market unencumbered by state regulation, one which accelerated “the centralization of power in the Federal Government, the obliteration of State lines, and the degradation of the State judiciary,”56 as one contemporary opponent of the federal courts described it.

Justices in this era would occasionally cite the benefits of an integrated national market explicitly in these decisions.57 But their belief in the importance of integrated national systems was most visible in their treatment of corporate receivership. Before the 1880s, insolvent railroads were typically broken up and their assets liquidated for the benefit of bondholders. But as the scale of the major interstate railroads grew, railroad managers began petitioning federal courts for receivership even before default, hoping to ward off dismemberment. Judges obliged. Beginning in the 1880s, federal judges began to protect managers by appointing them as receivers of their own companies, subordinating creditor rights to the larger imperative of maintaining a nationally integrated system of rail lines.

The overleveraged industry embraced the new arrangement: twelve of the nation’s twenty-eight largest railroad systems—firms that owned one-third of all American railroad mileage—entered “friendly” receivership. This allowed them to write off terrific amounts of debt: of the sixty-eight companies so reorganized between 1885 and 1900, the average firm slashed its fixed charges by 34 percent as it passed through receivership!58 In the words of legal scholar E. Merrick Dodd, “the tendency [of the legal environment] was to permit a capitalist to combine a considerable measure of control over a business with a sharing in its profits without becoming responsible for its debts.”59 This was a setting favorable to the progress of capital-intensive technologies and the expansion of industrial infrastructure.

The politicians of the new establishment did their part to create a macroeconomic environment equally conducive to techno-nationalist development. Their chosen political vehicle was, naturally, the victorious party of Lincoln. The GOP regularly endorsed a Hamiltonian vision of America’s future. Because, as James Garfield put it, “the civil society of our country is honeycombed through with disintegrating forces,”60 the United States was in desperate need of a strong centripetal force, which is exactly how most Republicans saw industry. Benjamin Harrison articulated a common belief when he argued that the new industrial economy was “working mightily . . . to efface all lingering estrangements between our people.”61

For two generations, Republicans used the powers of the American state to strengthen this new national industrial order. Republican congressional majorities offered more than 120 million acres—more than double the area of Virginia—in land grants to transcontinental telegraph and railroad companies.62 They built a wall of tariffs to protect American manufactures, especially the producers of iron and steel.63 Republican presidents appointed friendly justices to the federal courts (in the year of the Wabash and Santa Clara County decisions, all nine justices on the U.S. Supreme Court had been appointed by Republicans).64

These presidents also maintained America’s commitment to the gold standard against a tidal wave of populist agitation against it. This was particularly important to industrial interests dependent on foreign investment, such as the railroads. The scale of this investment was substantial. By 1895, the value of British railway bond holdings exceeded the annual expenditure of the U.S. federal government. And there was widespread fear that foreign investors would dump American securities if the United States abandoned the gold standard for greenbacks or free silver.65 Republican statesmen had to justify this monetary status quo to a national constituency all throughout the late nineteenth century, something they did with great zeal.

The Republican Party of this era was a political alliance between the Protestant clergy and the petit bourgeois of small-town New England and New York; the prosperous farmers of the Midwest, many of whom were Union veterans; and the new Eastern Establishment.66 The policy suite enacted by the GOP benefited each of these groups. Protective tariffs not only favored the large industrialists, but also smaller manufacturers across the North. Industries like wool were given special carve-outs in order to keep their producers in the Republican column. Tariff revenues, in turn, were used to fund generous pensions to Union veterans.67 These commitments often extended beyond government policy into acts of private patronage, such as when, during a federal budget shortfall, J. P. Morgan personally lent $2.5 million to the Army payroll to ensure that the payment of veteran pensions would continue, or when George Westinghouse underwrote the national gathering of five thousand chapter leaders of the Grand Army of the Republic in his hometown.68

The magnates of the Gilded Age grasped a lesson their twenty-first-century successors have largely forgotten. Technological development is only possible when a governing coalition commits to it; potential coalition members must be courted and convinced.69

The Eastern Establishment understood its project in generational terms. They knew that the integration of the American nation and the growth of American power would not be accomplished in their lifetime. They wanted their children to inherit their select position in American society—and to be worthy of that inheritance. These anxieties came to a head in the 1880s, as the first generation with no memory of the Civil War came of age. During this decade, New England boarding schools like St. Paul’s reinvented themselves as national preparatory academies for the sons of the industrial elite, drawing students from New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio.70 In their wake came a crop of new boarding schools—Lawrenceville (1883), Groton (1884), Hotchkiss (1892), Choate (1896), St. George’s (1896), Middlesex (1901), and Kent (1906)—each catering to a nationally defined upper class.71

Ivy League universities would follow suit. In the 1870s, Harvard instituted a standardized test for admissions that could be administered outside of Boston. By 1880, applicants were sitting for them in New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, and California. Alumni clubs were sprouting up in America’s major cities just as quickly, and the Board of Overseers soon opened to Harvard graduates living outside of Massachusetts.72 The result was a truly national institution and a reliable training ground for corporate America. On any given year between 1860 and 1900, between one-quarter and one-half of all Harvard students studied business.73

These institutions were not, and could never be, a complete replacement for the Civil War experience, though they did seek to cultivate the virtues the Civil War generation revered, such as patriotism, self-discipline, rationalism, professional competence, and physical courage.74 Just as importantly, they gave the children of a geographically dispersed elite a shared background, a common set of expectations, and enduring social bonds. Social clubs, intermarriage, and business partnerships reinforced these ties, allowing the Establishment to act with coherence and confidence long after the war had faded from living memory.

The economic, social, and political activities of the Eastern Establishment were mutually reinforcing pillars of a larger program. Members of the Establishment used the wealth generated by new technologies to secure political influence, used that influence to sustain a national market and legal framework geared for yet more technological expansion, and then presided over a conscious effort to preserve and transmit the values of their class to future generations, ensuring that the unity and discipline they gained in shared struggle would not dissipate amid power and prosperity. Through these means, a techno-nationalist elite guided America’s development for more than seventy years. Under its stewardship, the United States became the world’s wealthiest, most industrially advanced, and most powerful nation: a true technological republic.

A New Techno-Nationalist Elite?

This historical review offers uncomfortable lessons for those who dream, as Alexander Karp and Nicholas Zamiska do, of a twenty-first century techno-nationalist elite. The Technological Republic’s call for a “union of the state and the software industry” is, at bottom, a call for a new governing class.75 Any governing class requires three things: a political coalition to which it owes allegiance and over which it exercises influence; an economic base that provides this class with wealth and unites its members around shared material interests; and finally, a set of institutions, rituals, and social customs that give this class a culture distinct from the country at large. Absent the first two, a leadership class lacks the power to lead; absent the latter two, it lacks the ability to act as a class. The Eastern Establishment’s seventy-year dominance rested on its possession of all three.

It is not enough, therefore, to advocate for “a closer alignment of vision” between Silicon Valley and the state without asking what economic, political, and cultural arrangements could make such an alignment possible.76 The Technological Republic suggests that the federal government could profit from Silicon Valley’s organizational ingenuity, but it does not suggest how elected officials or federal bureaucrats might gain that expertise firsthand. It argues that technologists must identify with the American nation-state, but it never explains how this culturally progressive, immigrant-heavy industry might actually do so.

Part of Karp and Zamiska’s problem lies in how they conceive of this task. The Technological Republic speaks of the fusion of a “sector” and a “state,” but sectors and states are abstractions; what must be fused are people. This was also true for America’s first techno-nationalist elite. Behind the Eastern Establishment stood a dense web of personal ties that bound its families together. Many of these ties were consummated, quite literally, on the marriage bed. Karp and Zamiska are loathe to think in these terms. They write a great deal about the engineering elite’s waning commitment to Western civilization, but they have little to say about its waning commitment to raising the next generation of that civilization. The Eastern Establishment was self-consciously reproductive: it built schools, endowed universities, and founded literal dynasties. Part of building “a shared culture . . . that will make possible our continued survival” is creating the children who will survive us.77

The only concrete suggestion Karp and Zamiska offer for stopping the “most talented minds of our generation [from] splintering off . . . from the nation” is to restore “a core curriculum situated around the Western tradition” in America’s top universities.78 To this end, an entire chapter of the Technological Republic is spent relitigating the “canon wars” of the 1980s. This is thin gruel. If John Calhoun lacked national feeling, it was not for want of reading Plato and Homer, nor can the public-spirited ethos of the old Eastern Establishment be chalked up to a reading list. It was first forged in total war. It was later passed on and maintained through a lifelong system of education and socialization that started with the spartan boarding schools of youth and culminated in restrictive codes of behavior that governed all adulthood. A two-semester survey of the Western canon is no substitute for a way of life.

Karp and Zamiska recognize that Silicon Valley’s engineering elite lack the cultural confidence to defend any way of life. In a revealing passage, they lament that America’s technologists shy away from “the vital yet messy questions of what constitutes a good life, which collective endeavors society should pursue, and what a shared and national identity can make possible.”79 This fundamentally misdiagnoses the problem, however. Silicon Valley’s failing is not that its leaders refuse to ask such questions: it is that they refuse to answer them. Here Karp and Zamiska cannot escape the disease they so confidently diagnose. They insist that “the reconstitution of a technological republic will require a reassertion of national culture and values” but never tell us what those values are.80 They lament that Silicon Valley has been swallowed by “narrow and thin utilitarianism,” yet they do not articulate a richer moral vision to replace it.81 There is no passage in the Technological Republic that attempts to “define the good life” or “describe what a shared national identity can make possible.”

The technologists of an earlier century were not so reticent. They spoke frankly about their understanding of duty, hierarchy, patriotism, and moral standards. They preached an ethic of service to the nation that both sustained their power and defined its use. So confident were they in their vision of American life that it not only defined the worldview of their children and grandchildren but gave those descendants the ambition to “Americanize” the rest of the country, and, in time, much of the globe.

One looks in vain for such confidence in The Technological Republic. Karp and Zamiska devote entire chapters to urging the American public to tolerate corporate leaders who are strange, discomforting, or corrupt. They argue that too many of these leaders “are reluctant to venture into the discussion, to articulate genuine belief . . . for fear that they will be punished in the contemporary public sphere.”82 There is nothing objectionable in that argument, but it is painfully procedural. When Karp and Zamiska lament that that too many “founders say [they] actively seek out risk, but when it comes to public relations and deeper investments in more significant societal challenges, caution often prevails,” they could be describing themselves.83 They demand a pulpit for America’s technologists but never summon the courage to state what gospel they should preach.

Large passages of The Technological Republic thus read as a throat clearing exercise in place of substantive content that never arrives. Karp and Zamiska correctly observe that “an overly timid engagement with the debates of our time will rob one of the ferocity of feeling that is necessary to move the world.”84 But the book itself refuses to engage in any of the “debates of our time.”

To pick a timely controversy, what is the dispute over H-1B visas if not a debate over the very questions Karp says Silicon Valley must confront: “what is this country, what are our values, and for what do we stand?”85 Karp abstains from staking a position in this debate, or in any of the dozens of debates that touch on technology’s relationship to “substantive notions of the good or virtuous life.”86 What is his vision for America’s place in the world? What principles should govern the relationship between artificial intelligence and the American polity? Does transhumanism violate or embody the “shared purpose and identity” Karp and Zamiska believe we must forge? If what we need is a “larger project for which to fight,”87 then what precisely should that project be?

America’s first techno-nationalist elite did have such a project. Many of them died fighting for it. The industrial civilization they built would have been impossible without their ironclad commitment to America’s national greatness. Judged by that standard, Karp and Zamiska’s arguments are intolerably thin. “Those who say nothing wrong,” Karp and Zamiska warn, “often say nothing much at all.”88 The Technological Republic says nothing wrong and nothing much at all.

This article originally appeared in American Affairs Volume IX, Number 4 (Winter 2025): 108–31.

Notes

The author wishes to thank “Dean Marshall,” an attorney based in Washington, D.C., for his assistance in writing this essay.

1 A fact more generally recognized and celebrated outside of America than inside it. For examples, see: Thomas Hughes, American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm (New York: Penguin Books, 1989), 249–355.

2 See: Vaclav Smil, Creating the Twentieth Century: Technical Innovations of 1867–1914 and Their Lasting Impact (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); Vaclav Smil, Transforming the Twentieth Century: Technical Innovations and Their Consequences (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

3 Nadia Asparouhova, “Rewriting the California Ideology,” American Affairs 9, no. 2 (Summer 2025): 209–21.

4 Alexander Karp and Nicholas W. Zamiska, The Technological Republic: Hard Power, Soft Belief, and the Future of the West (New York: Crown Currency, 2025), 219.

5 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 74.

6 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 107.

7 Alexander Hamilton, “Alexander Hamilton’s Final Version of the Report on the Subject of Manufactures, [5 December 1791],” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed October 2025; Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 10, in The Federalist Papers, ed. Yale Law School—The Avalon Project, accessed October 2025. For a longer exposition of Hamilton’s proposed system, see: Edward Meade Earle, “Adam Smith, Alexander Hamilton, Friedrich List: The Economic Foundations of Military Power,” in The Makers of Modern Strategy: Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, ed. Peter Paret (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), 217–65.

8 E. Digby Baltzell, Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class (Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, 1958), 384–85; Peter Hall, The Organization of American Culture, 1700–1900: Private Institutions, Elites, and the Origins of American Nationality (New York: New York University Press, 1984), 218–19; William Freehling, The Road to Disunion, vol I: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), passim, but especially 9–37.

9 The transportation and communication networks of the early republic are described in: Daniel Walker Howe, What God Hath Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 40–41, 212–26.

10 Hall, The Organization of American Culture, 81–88; John Ingham, The Iron Barons: A Social Analysis of an American Urban Elite, 1874–1965 (Westport, Conn: Greenport Press, 1978), 22, 147. In Charleston, marriages between the state’s lowland and piedmont planter elites were viewed as bridging two fundamentally different cultures. See: William Freehling, Prelude to the Civil War: The Nullification Controversy in South Carolina 1816–183 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 19–24.

11 David McCullough, Mornings on Horseback: The Story of an Extraordinary Family, a Vanished Way of Life, and the Unique Child Who Became Theodore Roosevelt (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981), 199. See also comments on Princeton in: Ingham, Iron Barons, 95.

12 Christopher Grandy, “New Jersey Corporate Chartermongering, 1875–1929,” Journal of Economic History, 49, no. 3 (1989): 677–92.

13 Hall, The Organization of American Culture, 241–42.

14 David Hacket Fisher, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989); E. Digby Baltzell, Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia, (1979; reissued, New York: Routledge, 2017), 57–177.

15 Howe, What God Hath Wrought, 136–37.

16 Howe, What God Hath Wrought, 164–203; Baltzell, Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia, 364–66; Robert Swierenga, “Ethnoreligious Political Behavior in the Mid-Nineteenth Century: Voting, Values, Cultures,” in Religion and American Politics: From the Colonial Period to the Present, eds. Mark Noll and Luke E. Harlow (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 144–68.

17 For a prominent example, see: Daniel Webster, The Webster-Hayne Debate on the Nature of the Constitution: Selected Documents, ed. Herman Belz (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2000).

18 The Jacksonian party system reinforced the localist tendencies of Jacksonian ideology. Leaders of the Whig and Democratic parties were localists by necessity, not national organizations but loose networks of local political machines. Through the 1880s, national party committees were weak or nonexistent. National leaders were chosen through pyramidal nominating conventions, which empowered local bosses. The spoils system, rooted in geography, handed patronage to congressmen and party bosses rather than the president, further entrenching parochial interests. In the words of historian Daniel Klinghard, the system was “designed to empower the preferences of state and local organizations” over the concerns of the national electorate.

See: Daniel Klinghard, The Nationalization of American Political Parties, 1880–1896 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 25–66, 191–235. Here, as elsewhere, this would change when leaders of the Eastern Establishment built a new set of national institutions at the tail end of the Gilded Age.

19 Howe, What God Hath Wrought, 221–22; Freehling, Prelude to the Civil War, 98–9, 118, 256.

20 As quoted in: Lawrence Frederik Kohl, The Politics of Individualism: Parties and the American Character in the Jacksonian Era (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), 28, 141; James M. McPherson, The Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 99.

21 Sven Beckert, The Monied Metropolis: New York City and the Consolidation of the American Bourgeoisie, 1850–1896 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 20–97, especially 60–64, 87–88.

22 Noam Maggor, Brahmin Capitalism: Frontiers of Wealth and Populism in America’s First Gilded Age (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017), 22, 26–30, 34–35, 50.

23 Quoted in: Kohl, Politics of Individualism, 138.

24 On the consolidation of the Northern regional elites during and immediately after the war, see: Hall, Organization of American Culture, 275–89; on the industrial elite, see: Beckert, The Monied Metropolis, 115–32, 135–37, 148–58.

25 Richard Franklin Bensel, Yankee Leviathan: The Origins of Central State Authority in America, 1859–1877 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 233–34, 416–20. Their allies in the Northern textile mills and New York merchant houses were likewise forced either to anchor their fortunes elsewhere or sink into decline. See: Maggor, Brahmin Capitalism, 8–10; Beckert, Monied Metropolis, 120–21, 151–54, 164–71.

26 Leonard P. Curry, Blueprint for Modern America: Nonmilitary Legislation of the First Civil War Congress (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1968).

27 Kessner, Capital City: New York City and the Men Behind America’s Rise to Dominance (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2003), 36–43; Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: The Organized War, 1863–1864 (New York: Scribner, 1971), 249–57; Beckert, The Monied Metropolis, 136–37.

28 Long after becoming one of the most successful bankers on Wall Street and an adviser to several Republican governments, Henry Clews remembered his participation in Union War financing as the most significant accomplishment of his career. He would memorialize his profession’s participation in war financing with the following words: “There was patriotism worthy of Patrick Henry, as well as profit, in this. . . . As General Grant said long afterwards to me, we were not fighting for the Union as soldiers in the field, but we served it equally well by helping it in its struggle for money to prosecute the war; and I felt proud of the active part I took in thus helping to preserve the Union as one of its army in civilian life.” See: Henry Clews, Fifty Years in Wall Street: “Twenty-Eight Years in Wall Street,” Revised and Enlarged by a Résumé of the Past Twenty-two Years, Making a Record of Fifty Years in Wall Street (New York: Irving Publishing, 1908), xlii–xliii, 91.

29 He was not entirely successful; in Vincent Carrosso and Rose Carasso’s judgement, Morgan’s activities brought his firm “added recognition and the satisfaction of contributing to the Treasury’s efforts to reorganize the debt” but did not result in profits. See: Vincent Carrosso and Rose Carasso, The Morgans: Private International Bankers, 1854–1913 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974), 94–114

30 Beckert, Monied Metropolis, 150.

31 Rockefeller was not yet the oil magnate he would soon become, but a prosperous shipper of dry goods. See: Ron Chernow, Titan: The Life of John Rockerfeller, Sr., 2nd ed. (New York: Random House, 2004), 87.

32 Baltzell, Philadelphia Gentlemen, 345.

33 In both cases, the Union League Club did this in conjunction with other associations: the Loyal Publication League and Loyal League of Union Citizens, for the first; the New York Association for Promoting Colored Volunteering, for the second. The membership of these organizations drew from an overlapping set of wealthy activists in which manufacturing magnates like Peter Cooper dominated. See: Beckert, Monied Metropolis, 131, 134–35.

34 Beckert, Monied Metropolis, 116. The committee was initially funded solely by donations from wealthy New Yorkers and the New York Chamber of Commerce; by the end of the war, it would also draw from the New York City municipal budget.

35 Allan Nevins, The Organized War, 1863–1864, 317–23; on the class background of the Commissions’ leaders, see: George Frederickson, The Inner Civil War: Northern Intellectuals and the Crisis of the Union, rev. ed (Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 99-100.

36 Louis Menand, The Metaphysical Club (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001), 67.

37 Hall, Organization of American Culture, 270–71.

38 Hall, Organization of American Culture, 270.

39 Frederickson, Inner Civil War, viii, 173–76. On the question of the railroad influence on Army organizational practice, see: Hall, Organization of American Culture, 280–87; on the impact military service had on late nineteenth century corporate culture, see: Nevins, The Organized War, 1863–1864, 329–30.

40 This generational conflict in ideals is explored in: Frederickson, Inner Civil War, passim, but especially 173–76; Menand, The Metaphysical Club, 3–69.

41 William H. Seward, The Works of William H. Seward, Vol. 1 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1884), 384.

42 Henry Clews, Fifty Years in Wall Street, 6. This generational turnover in financial and industrial circles during the 1860s is also emphasized in: Maggor, Brahmin Capitalism, 36–40; Beckert, Monied Metropolis, 123.

43 Michael Allsep Jr., “New Forms for Dominance: How a Corporate Lawyer Created the American Military Establishment,” PhD diss. (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2008), 129.

44 Senator John Sherman described their vision as such: “The truth is, the close of the war with our resource unimpaired gives an elevation, a scope to the ideas of leading capitalists, far higher than anything ever undertaken in this country before. They talk of millions as confidently as formerly of thousands… our manufacturers are yet in their infancy, but soon I expect to see, under the stimulus of great demand and the protection of our tariff, locomotive and machine shops worthy of the name.” Quoted in: Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: The Organized War to Victory, 1863–1864 (New York: Scribner, 1971), 373.

45 Maggor, Boston Brahmins, 9.

46 Kessner, Capital City, 46–7; Beckert, The Monied Metropolis, 145.

47 Richard Franklin Bensel, The Political Economy of American Industrialization (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 295.

48 James Beniger, The Control Revolution: Technological and Economic Origins of the Information Society (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1986), 219–91.

49 Alfred D. Chandler, The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1977), passim, but especially 81–122; 145–188. See also: Gerald Berk, Alternative Tracks: The Constitution of American Industrial Order, 1865-1917 (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1994), 1–2, 12–13, 65–71; Bensel, Political Economy, 314–18.

50 Kessner, Capital City, 285–335; Chandler, Visible Hand, 315–44.

51 Kessner, Capital City, 298.

52 Between 1789 and 1865, for example, Connecticut passed something like three thousand special acts incorporating every conceivable kind of social and economic organization. See: William J. Novak, “Putting the ‘Public’ in Public Administration: The Rise of the Public Utility Idea,” in Administrative Law from the Inside out: Essays on Themes in the Work of Jerry L. Mashaw, ed. Nicholas R. Parrillo (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 373–97.

53 E. Merrick Dodd Jr., “American Business Association Law a Hundred Years Ago and Today,” in Law: A Century of Progress 1835-1935, Vol. 1, ed. Alison Reppy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1937), 254–84; Grandy, “New Jersey Corporate Chartermongering.”

54 Quoted in: Bensel, Political Economy, 327; this passage draws in his broader discussion from 321–54. See also: Berk, Alternative Tracks, 58–60, 156–58.

55 Bensel, Political Economy, 336.

56 Quoted in: Tony Freyer, “The Federal Courts, Localism, and the National Economy, 1865–1900,” Business History Review 53, no. 3 (Autumn, 1979):

359–60.

57 Consider, for example, Justice Samuel Miller’s decision in Cook v. Pennsylvania (1878), striking down a Pennsylvania law that taxed the sale of out-of-state goods sold at auction, which reads in part: “If certain states could exercise the unlimited power of taxing all the merchandise which passes from the port of New York through those states to the consumers in the great west, or could tax—as has been done until recently—every person who sought the seaboard through the railroads within their jurisdiction, the constitution would have failed to effect one of the most important purposes for which it was adopted.” Quoted in: Bensel, Political Economy, 325.

58 Berk, Alternate Tracks, 65.

59 Dodd, “American Business Association Law,” 258.

60 Quoted in: John Gerring, Party Ideologies in America, 1828–1996 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 99.

61 Benjamin Harrison, Speeches of Benjamin Harrison, Twenty Third President of the United States (New York: United States Book Company, 1892), 142. See also James G. Blaine’s comments about the “spirit of industrial enterprise” and the “unification of financial interests” in: James G. Blaine, Twenty Years in Congress, (Norwich, Conn.: Henry Bill Publishing, 1884), 671.

62 This was accompanied by loans for $16,000 per mile (for construction on the plains) and $48,000 per mile (in the mountains) of government bonds to the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads. See: H. W. Brands, American Colossus (New York: Knopf Doubleday, 2011), 49.

63 Bensel, Political Economy of American Industrialization, 8–18, 205–88, 457–509.

64 Moreover, seven of these were from the Northeast. See: Bensel, Political Economy of American Industrialization, 344–55. Railroad executive Charles Elliot Perkins thought that this was the most important role of the GOP. As he wrote in one letter, “There are so many jack-asses about nowadays who think property has no rights, that the filling of the Supreme Court vacancies is the most important function of the presidential office,” See: Freyer, “The Federal Courts, Localism, and the National Economy,” 346.

65 Bensel, Political Economy of American Industrialization, 355–456.

66 On the origins of this coalition, see Richard Cawardine’s account of the election of 1864 in: Richard Cawardine, Lincoln: A Life of Purpose and Power (New York: Knopf Doubleday, 2007), 249–310. Also see: Phillip Shaw Paludan, “War Is the Health of the Party: Republicans in the American Civil War,” in The Birth of the Old Grand Party, eds. Robert F. Engs and Randall M. Miller (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), 60–81. On the maintenance of this coalition through the Gilded Age, see: Bensel, Political Economy, 130, 490–5, 502–6; Robert Marcus, Grand Old Party: Political Structure in the Gilded Age, 1880–1896 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971).

67 Bensel, Political Economy, 487–502.

68 Kessner, Capital City, 217–218; William Huber, George Westinghouse: Powering the World (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, 2022), 223–24.

69 The leaders of nineteenth century industry did not just seek to materially reward coalition members but also built institutions to persuade coalition members of the value of favored policies. Consider the example of the American Iron and Steel Association, the million tracts it distributed in the run-up to the election of 1888 and the network of “question clubs” it founded across American towns devoted to debating tariff policy. See: Klinghard, The Nationalization of American Political Parties, 76–81.

70 Ingham, The Iron Barons, 93–94, 148, 217; Baltzell, Philadelphia Gentleman, 307–12.

71 Baltzell, Philadelphia Gentleman, 306.

72 Hall, The Organization of American Culture, 321–22. Similar reforms occurred across the Ivy League

73 Hall, The Organization of American Culture, 289.

74 Jerome Karabell, The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Princeton, and Yale (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005), 27–38.

75 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 27.

76 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 53–54.

77 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 243.

78 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 154, 106–7.

79 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 14–15.

80 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 31.

81 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 53–54.

82 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 17.

83 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 69.

84 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 64.

85 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 95.

86 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 231.

87 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 250, 96.

88 Karp and Zamiska, The Technological Republic, 85.

About the Author

Tanner Greer is a writer and deputy director of the Open Source Observatory at the Council of Foreign Relations.

ᵛ the agora. Athens, southern Europe/ eastern Mediterranean Sea region, circa 400 years before the Common-era